Helping immigrant children find stability after dangerous journeys

At first glance, Nathaly seems like any other 16-year-old – shy around strangers, weary in the way over-busy teenagers can be, and ping-ponging steadily to and from her computer screen as the virtual school days at her North Jersey high school demand.

At first glance, Nathaly seems like any other 16-year-old – shy around strangers, weary in the way over-busy teenagers can be, and ping-ponging steadily to and from her computer screen as the virtual school days at her North Jersey high school demand.

Poverty widespread

But just a year ago, life was very different. Nathaly lived with her family in Ecuador, where the coronavirus pandemic worsened poverty’s longtime stranglehold on the South American country. More than 52 percent of Ecuadorians now live in poverty, by some estimates, with school dropout and child labor rates rising. (In comparison, the U.S. poverty rate is about 12 percent.) Pregnant at 15, Nathaly feared the future.

Without a word to her family, she left home last December, her sights set on a better life in the United States. Twelve years ago, her aunt Betty had made a similar decision. Betty’s journey across the border had been perilous, but she’d since built a safe, comfortable life in North Jersey. Wanting the same for her niece, she bought Nathaly a plane ticket to Mexico – and prayed for God to protect her as she traveled alone by bus and foot the remaining distance to Texas.

The journey through Mexico took seven days. Along the way, Nathaly met two other teen émigrés, and they drew strength from each other as they navigated the harsh desert and carefully avoided strangers in Juárez, a border city with a violent history especially for women. At the Texas border, they found a dry river bed to cross, and the brighter future they’d suffered for at last seemed within their grasp.

Then Border Patrol swarmed. The immigration agents caught all three girls and put them in immigration detention shelters, where a judge would decide their fate. Nathaly, though, felt only relief.

“At least we’re going to be alive,” thought Nathaly, who was eight months pregnant during her grueling trek.

Immigrant children more vulnerable

For many immigrants caught after entering the U.S. without documentation, deportation can be an unavoidable fate. But for unaccompanied minors like Nathaly, the future is a bit more complicated. Federal law mandates protective procedures for them, recognizing the higher risks that they, as vulnerable children, face of exploitation, trafficking, or violence. And a new federal policy enacted in February aims to speed up their release and reunification with their families.

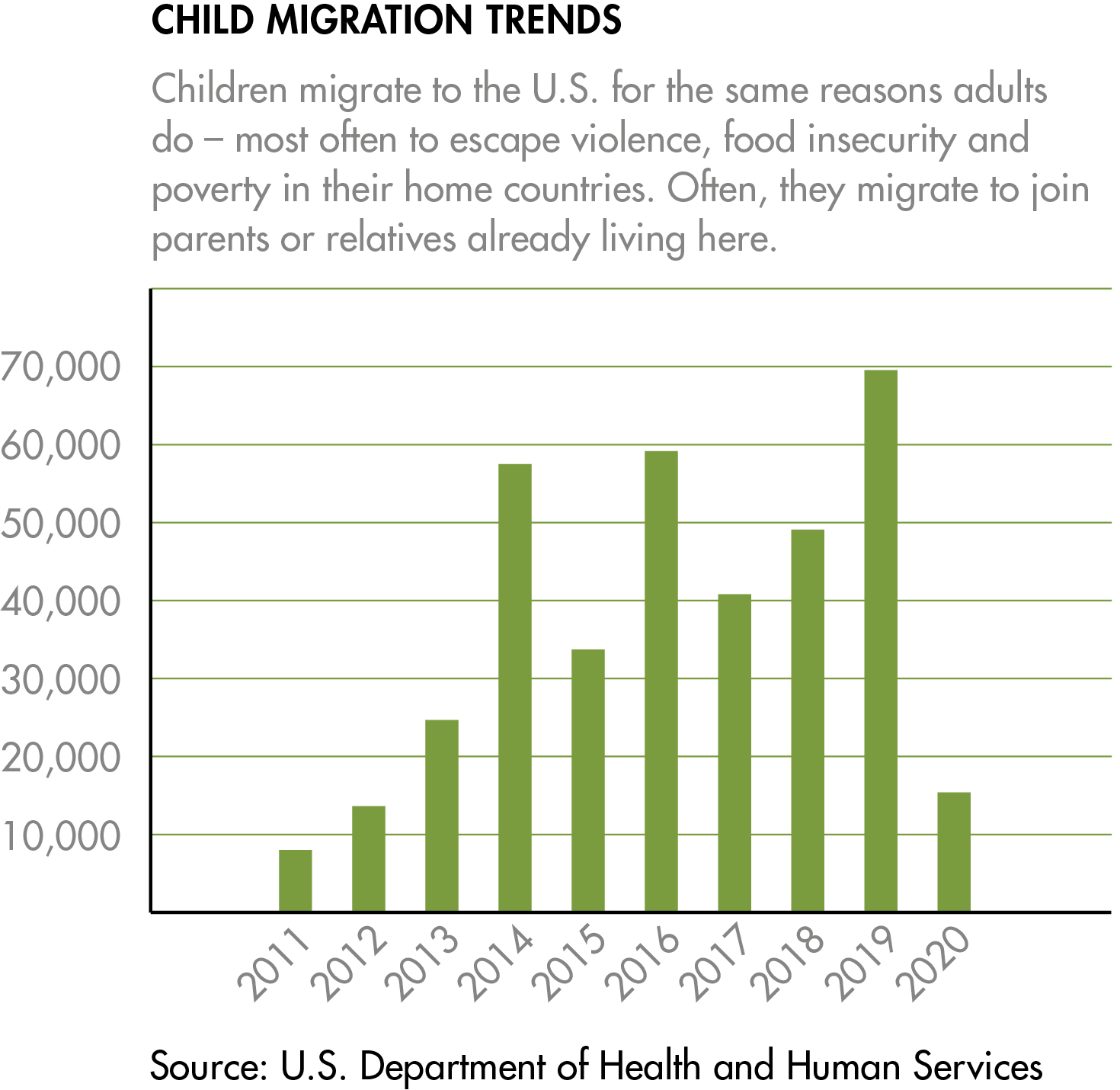

That’s where the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops (USCCB) comes in. The USCCB created a program called Safe Passages that reunites unaccompanied, undocumented minors who have been apprehended by immigration authorities with sponsors in the U.S. (typically family members). In New Jersey, Catholic Charities, Diocese of Trenton steps in after that reunion to provide services statewide that help the children find stability and normalcy as their immigration cases proceed through the legal system. The need is acute: In March alone, Border Patrol apprehended nearly 19,000 unaccompanied children at the border, a record since at least 2009, according to federal figures.

At Catholic Charities, Marilyn Zeno (pictured above, beside Nathaly, Betty, Nathaly’s baby and Betty’s daughter) oversees the program, which is based at Community Services in Lakewood and has been in place since 2012. Catholic Charities helped about 70 children last year and so far this year in New Jersey through Safe Passages.

Stability the goal

“We provide them all the resources and referrals they need to move on,” Zeno said. “For example, if you are undocumented, you don’t have insurance. So we help them apply for charity care to cover medical bills. We help them enroll in school. We help them get ID. If mental health is a concern, we connect them with guidance counselors and mental health care. We help them connect with pro bono attorneys to handle their case. We do whatever we can to help them find stability and safety here.”

For Nathaly, that meant transferring her immigration case from Texas to New Jersey, where she now lives with her aunt. It also meant ensuring she got obstetric and pediatric care for the baby boy she gave birth to in February.

Nathaly wants to stay in the U.S. and become a citizen. She dreams of someday becoming a doctor. But the baby is her overriding purpose now.

“I want to finish my education so I can give my son what I never had in Ecuador,” she said.

Subscribe for more news

FOR INFORMATION on Safe Passages, contact Program Supervisor Daniel Correa at (732) 363-5322 or [email protected] or Dana DiFilippo, communications, at [email protected] or (215) 756-6277.

To subscribe to our blog posts and news releases, fill out the fields below.